Quick word association: I say “club” and you say … what? “Comedy?” “Fitness?” “Strip?”

Ten and 12 decades ago, your answer would have been very different: clubs like the Rosecrans or Friday Morning Club, or — if you were flush with money, white, male and invited — California or Jonathan.

A couple of hundred private clubs flourished in Los Angeles in the 1920s, more than a dozen of them along the beachfront. Some of them date to the 19th century, and a few of those are still with us.

The new ones tend to be “lifestyle” clubs, second homes for fitness, food, recreation, serene workspaces and the company of like-minded and prosperous people. Come to think of it, if you substitute hot yoga and Kingsman suits with smoking jackets and the noble game of billiards, present-day “lifestyle” clubs are not too unlike the London men’s club culture of gaslight and Mycroft Holmes —Sherlock’s older, smarter brother, unfailingly found at the Diogenes Club.

The L.A. of 1900, 1910, 1920 didn’t go in for bowling alone. Angelenos wanted to belong.

People who moved here to get away from where they came from immediately sought out people from the same place and organized into associations and clubs. The annual Iowa Picnic used to draw 100,000 people; 120 years later, it still attracts Hawkeye Angelenos, but in much-diminished numbers. Service clubs found welcoming soil here. In 1909, the Elks, in a carousing frame of mind, staged their national convention here; the International Railway Journal called it “the biggest event for the best people in the prettiest town on earth.”

Clubs were so powerful a “tell” of a man’s or woman’s interests and status that obituaries listed the clubs they belonged to, usually more than one.

The earliest Los Angeles women’s clubs took on the tasks of political and social reform, which was unsurprising, because women were still years from the right to vote even in California. L.A.’s Friday Morning Club was the biggest chapter of the national General Federation of Women’s Clubs. Caroline Severance was already 60 years old when she founded the Friday Morning Club, in 1881. In time, she earned the nickname “the mother of clubs.” She was a friend and associate of Susan B. Anthony’s, and put her progressive stamp on the city, from its library to founding kindergartens.

Severance, like her husband, was also a ferocious abolitionist. But then came “the colored question”: Could Black women or their clubs join the white women’s? In 1902, Severance — by then 82 years old — punted, agreeing with the national organization that the matter should be left to each state’s clubs to decide.

Clark Davis, writing in the “Encyclopedia of Women in the American West,” noted that in 1914, at least 85% — 85%! — of noncareer white women in the nation belonged to at least one club.

But L.A.’s Black women, barred from joining those influential white clubs, created clubs of their own. The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine, dished out praise in 1912 that “Los Angeles is perhaps the greatest center of colored-club activity in California.” The Wilfandel Club, still in the West Adams district, was founded in 1945 by two women surnamed Williams: Fannie and Della, both formidable community leaders (Della was the wife of renowned architect Paul Williams). The club name combined syllables of their names. One of the club’s philanthropies is a scholarship named for Della Williams.

Turn-of-the-century women’s clubs devoted themselves to conditions in juvenile courts, the censorship of movies, Shakespeare, and fighting billboards, smoke and noise. The L.A. section of the National Council of Jewish Women organized committees on tuberculosis, the press, immigrant aid and hygiene education. The Rosecrans Club was dedicated to caring for women and children, “especially little unfortunates and poor cripples.”

Some women’s clubs “successed” themselves out of existence. Opportunities for college educations and new careers gave women public power and public voices they had not had before. They didn’t need clubs for leverage, inspiration or education, and so, according to Clark, “throughout the 1920s the culture of club life for affluent Los Angeles women had shifted from aggressive optimism over women’s broadening spheres to a more passive social-oriented elitism.’’

The Friday Morning Club’s first Figueroa Street home is seen on this postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection. Its second building, at 940 S. Figueroa St., is on the National Register of Historic Places.

()

A few clubs survived across three centuries; the Friday Morning Club closed in 2012, after 13 decades, and the 1894 Los Angeles Ebell Club, headquartered in a spectacular building in the Mid-Wilshire district, still delivers scholarship and philanthropic grants, and has hosted notable women from Amelia Earhart to Michelle Obama.

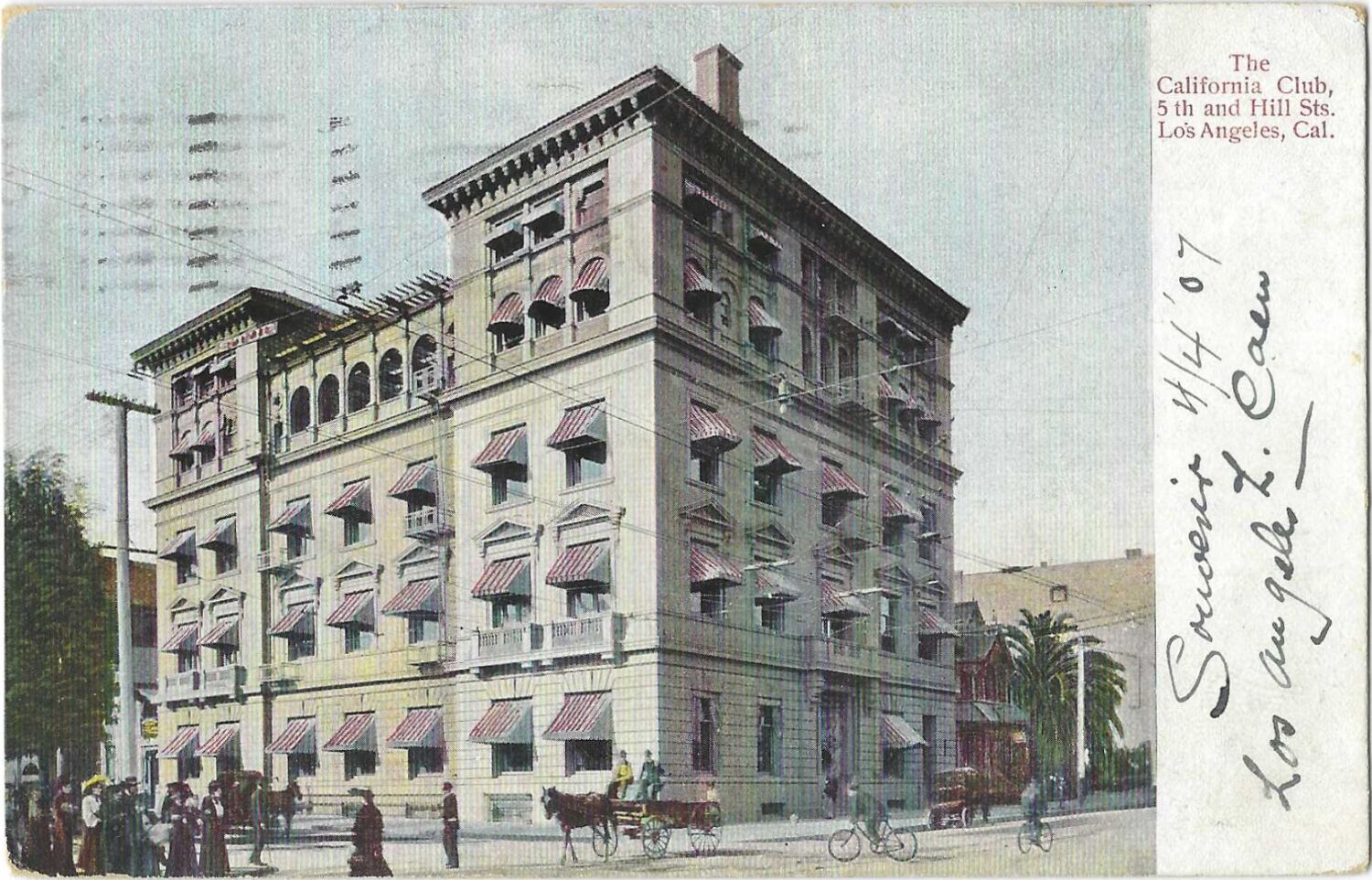

At the pinnacle of L.A.’s private club system is the California Club, founded in 1887, and the Jonathan Club, founded in 1895. According to a Times society story, a bunch of friends so enjoyed working together on William McKinley‘s presidential campaign that they made themselves into a permanent “purely social club.” The name “Jonathan” was taken from a caricature called Brother Jonathan, a precursor of Uncle Sam, an unmannered, forthright, patriotic New Englander.

(Disclosure: I have been a guest and a speaker at several of L.A.’s old-line clubs, including these two.)

Their magnificent buildings in downtown L.A. were citadels of white male Gentile privilege. For the California Club, this was a paradox, because Jews and Mexican Californios were among its founders. Yet within a few decades, as historian Kevin Starr wrote, “lines began to be drawn reflecting a less inclusive spirit.”

Had some of those founders applied for membership 40 years later, they would not have been admitted. The same standards held at the Jonathan Club.

The Elks held a convention in Los Angeles in 1909. The International Railway Journal called it “the biggest event for the best people in the prettiest town on earth.” An advertisement is seen on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

()

But almost 50 years ago, that began to change, after The Times printed a searing series on many private clubs’ practices, full of revealing incidents, and detailing how these two top clubs, as well as golf clubs, fortified themselves against even considering well-qualified applicants of color, Jews or — especially —women.

In a Catch-22 practice, such people were rarely nominated, because the clubs’ reputations discouraged members from suggesting candidates who would surely be rejected, and members didn’t want to come across as rabble rousers. Some decades ago, a member of the conservative Wilshire Country Club nominated FDR’s son James for membership. As The Times’ Pulitzer Prize-winning sports columnist, Jim Murray, told the story, not only was Roosevelt rejected, the member who nominated him was expelled for good measure. That same Roosevelt ran for mayor in 1965, and laid into the incumbent, Sam Yorty, for paying his dues to the segregated Jonathan Club with his city expense account.

In 1976, the visiting Air Force Academy choir was supposed to have a party at the Jonathan Club’s beach facility. It was canceled, as late as a few hours beforehand; one choir member was Black. Santa Monica was officially mortified; its council passed an apology resolution. That black cadet, Livingston Holder, went on to be an Air Force astronaut.

All of this scrutiny came about partly because in 1973, a Black sharecropper’s son, Tom Bradley, was elected mayor. L.A. mayors traditionally were invited to become honorary members of the California and Jonathan clubs. Bradley, it seems, was not. In the spirit of Groucho Marx’s bon mot about not joining any club that would accept him as a member, Bradley refused to set foot in either club, and helped to start the City Club, which has a quite diverse membership and which, from 51 floors up, literally looks down on the California Club across the street.

The California Club’s practices cost it a royal visit. In 1982, when Britain’s Prince Philip was scheduled to go to a party there on a trip to L.A., he went elsewhere after the British team learned that the club banned women members and had excluded minority members.

If you’re exiting the northbound 110 Freeway at 6th Street, look at the red brick building to your left: That’s the Jonathan Club, seen here on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

()

The rationales for the discriminatory practices make for uncomfortable reading nearly a half a century later.

“It was mentioned in a friendly way that the feeling of the majority of the club’s membership was that we don’t invite members of minorities. It’s not a big thing at all. They can come as guests anytime. It’s just the clannish thing — you know what I’m talking about. We are a little bit on the clannish side.”

— a Jonathan Club membership committee member to The Times in 1978, discussing a meeting with a prospective member who wanted to know about minority admissions, and who withdrew his application.(There were) “four or five or six Jewish members of the California Club in the mid-1970s, but “they may not be Jewish by both parents.”

— a California Club president to The Times in 1976.

The critics — not only of the two L.A. clubs but of many private male-dominated clubs of that period — argued that the clubs’ memberships were a kind of roll call of movers and shakers, that business was conducted there that influenced civic life and advanced the careers of members.

Excluding Jews, people of color and women shut them out of this networking and contacts-making. The clubs’ counter, that they were strictly social gathering places, was undermined by the fact that the membership fees for many members were paid for by their companies in the belief that good clubs were good for business.

The public attention began to change all of that. Organizations — businesses, banks, bar associations, government agencies — stopped holding meetings at the clubs and stopped paying members’ dues. State legislators made noises about threatening club liquor licenses. The state banned business tax deductions for money spent on private clubs that discriminated. Mayor Bradley signed Councilwoman Joy Picus’ ordinance banning discrimination by most private clubs for race, gender, religion or other factors.

The Los Angeles Athletic Club downtown is still in operation, with indoor fitness facilities, including a pool, and a hotel. It’s seen here on a postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

Lower-profile clubs paid attention. The Los Angeles Athletic Club had admitted women since the 1930s and some Black members since the early 1960s. But in the mid-1970s, women were still banned from its Grill Room sandwich bar. It took a call from one member — federal Judge Harry Pregerson — to another member — Gov. Jerry Brown — and within days, women were welcome in the grill.

In 1976, about two years after Harold Brown’s name was submitted for membership, and after a lot of internal lobbying by club members including Times publisher Otis Chandler and future Mayor Richard Riordan, Brown, who was Jewish, finally became a California Club member. He was a nuclear physicist, the president of Caltech, and, a year after his admission, the U.S. secretary of Defense. (The dialing-up of antisemitism after World War II was so vast that when Yale’s first Black football captain, Levi Jackson, was invited to join the swanky, secret Skull and Bones society, he remarked, “If my name had been Jackson Levi, I’d never have made it.”)

It took another 10 years before club memberships opened up to numbers of women; even after the state and local laws against discrimination were enacted, a rump faction at the California Club kept trying to change the house rules to skirt the new laws.

In 1987, L.A.’s Rotary Club admitted its first woman member, just a few years after the Duarte chapter had been expelled for doing the same. In early 1988, the California Club admitted its first Black member, Dr. Joseph Alexander, a surgeon and former Army colonel.

Attorney Gloria Allred, who has never minded breaking rules and a few egos in her campaigns for equality, broke the gender barrier at the Los Angeles Friars Club, the showbiz hangout, now closed, whose roster included Bob Hope, Sid Caesar and Billy Crystal.

Its first woman member was Allred, and she told me last week how it happened. “I asked a number of people to sponsor me, but they were afraid they’d be called troublemakers.” So as a lunch guest there one day, she approached club founder Milton Berle. “I introduced myself and said, I’d like to be a member of this club; would you sponsor me? And he said, why do you want to be a member? I said it’s because you have a really delicious Cobb salad.”

Berle asked if she wouldn’t settle for being an honorary member. “I said, ‘Mr. Berle, it would be a dishonor for me to be an honorary member of a club that discriminates against women.’”

Berle sponsored her membership, and not long thereafter, when she learned women were barred from the steam room, “I put on a Gay Nineties bathing suit and knocked on the (steam room) door. The men were in there naked and I pulled out a tape measure and started singing ‘Is That All There Is?’ and the men began grabbing towels and wrapping them around their butts. After that, women were allowed to use the steam room. I never went back to use the steam room. What I wanted was a change in policy, and they did that.”

Some of L.A.’s country clubs practiced the same exclusion en plein air. Writing for Golf Digest, The Times’ Murray opined that the requirements to join the Wilshire Country Club were “a Hoover (for president) button, a home in Pasadena, and proof-positive that you never had an actor in the family.”

Author Joseph Wambaugh wrote in The Times in 1975 about his search for a golf club near his San Marino home. Every one he found was restricted. At one club, a member told him, “Once we had a wedding reception at the club and they said there’d be no problem with our one Black guest — of course he had a PhD.” When he asked at another club about Latino members, a board member struggled to think of one, and finally said, “It’s none of your goddam business.”

At the Los Angeles Tennis Club, built in 1920, Black tennis star Arthur Ashe was only an honorary member in 1978 when Black attorney, Rhodes scholar, Yale law grad and future mayoral candidate Stan Sanders was turned down for membership. The city attorney’s office was unamused, and one member, Walter Ralphs, the retired head of the grocery store chain, quit, in part over the incident.

The state Supreme Court in the 1990s reinforced the nature of anti-discrimination rules that apply to most private clubs.

In the world of clubs, “actor” and “Hollywood” were often code words for Jews. A well-circulated story (with predictable variations) has Groucho Marx at poolside at a restricted club with a friend who’d invited him. A club official came up to tell Marx he was welcome to stay in his chair, but his little daughter would have to get out of the pool. She’s only half-Jewish, Groucho retorted; “Can she go in up to her waist?”

Marx did become a member of the Hillcrest Country Club in Cheviot Hills, founded by renowned Jewish film moguls and actors who were unwelcome at Gentile country clubs. Comedians such as George Burns and Danny Kaye joined Jewish business figures regularly, and there’s no telling how many millions were collected for Jewish charities in Hillcrest’s meeting rooms where — like the California Club — the food was, and remains, outstanding.

But Hillcrest, born to beat bias, was challenged for bias against single women members. At many country clubs, the only women members were associates, wives of full members, and when it came to tee times, women pretty much got leftovers. Hillcrest changed its bylaws to admit women members.

In The Times’ 1976 series, one nameless country club manager said, “The wives feel the single women would be a threat to them … they’re afraid they’ll take their husbands away, I guess.”

That barrier, too, was knocked down — or more like slow-mo toppled, inch by inch. In 1988, record-setting aviator Brooke Knapp, a former associate member, became the only regular woman member of the Bel-Air Country Club.

And so it went through the ’70s and ’80s and even into the ’90s. Defying the dismal predictions by the more fossil-minded members, the clubs did not implode as more Jews and people of color and, finally, women began to join their rarefied real estate.

The balance slowly tipped away from those personal identifiers to where it pretty much is today: resume and character qualifications — and whether you can pay.

On top of initiation fees — for top clubs, we’re talking a few to many tens of thousands — there is each month a membership fee and sundry charges on top of that. Such belonging is not for the faint of checkbook.

In 1981, billionaire tycoon David Murdock founded the members-only Regency Club on the 17th floor of his building in Westwood. Its invited members, like billionaire philanthropist Eli Broad, met and dined there until the club closed in 2011.

1/12

The former home of the Benevolent Order of the Elks is seen on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

2/12

The Elks held a convention in Los Angeles in 1909. The International Railway Journal called it “the biggest event for the best people in the prettiest town on earth.” An advertisement is seen on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

3/12

The Ebell Club, founded in 1894 and seen on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection, is still active.

4/12

A postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection bears a 1909 postmark and a note “from your naughty L.A. friend.” The Friday Morning Club’s second building, at roughly the same place where this one stood, is Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 196.

5/12

The Friday Morning Club’s first Figueroa Street home is seen on this postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection. Its second building, at 940 S. Figueroa St., is on the National Register of Historic Places.

6/12

A 1923-postmarked postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection shows the Woman’s Club of Hollywood building.

7/12

The Hollywood Athletic Club, which opened in 1924, is today a for-hire meeting and events space. Its Sunset Boulevard location is seen on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

8/12

The Los Angeles Athletic Club downtown is still in operation, with indoor fitness facilities, including a pool, and a hotel. It’s seen here on a postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

9/12

The text on the reverse side of this postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection says, “Corner of Beefsteak Room, Los Angeles Athletic Club.”

10/12

A view of the Jonathan Club’s downtown L.A. rooftop on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

11/12

If you’re exiting the northbound 110 Freeway at 6th Street, look at the red brick building to your left: That’s the Jonathan Club, seen here on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection.

12/12

The California Club’s former building is seen on a vintage postcard from Patt Morrison’s collection. Today, the club’s members gather on Flower Street.

Private beach clubs still flourished. Though California generally owns the beach seaward from the mean high tide line, private owners can still claim beach property.

Marion Davies, the actress and mistress of publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst, had an enormous Santa Monica beachhouse, and when I say enormous, I mean scores of rooms, 37 fireplaces, dinner seating for 25, and one chamber done up in gold leaf. In about 1960, Santa Monica took over part of it and leased it for 30 years to the Sand & Sea membership club.

https://globalcourant.com/patt-morrison-the-naked-truth-about-l-a-s-swanky-private/